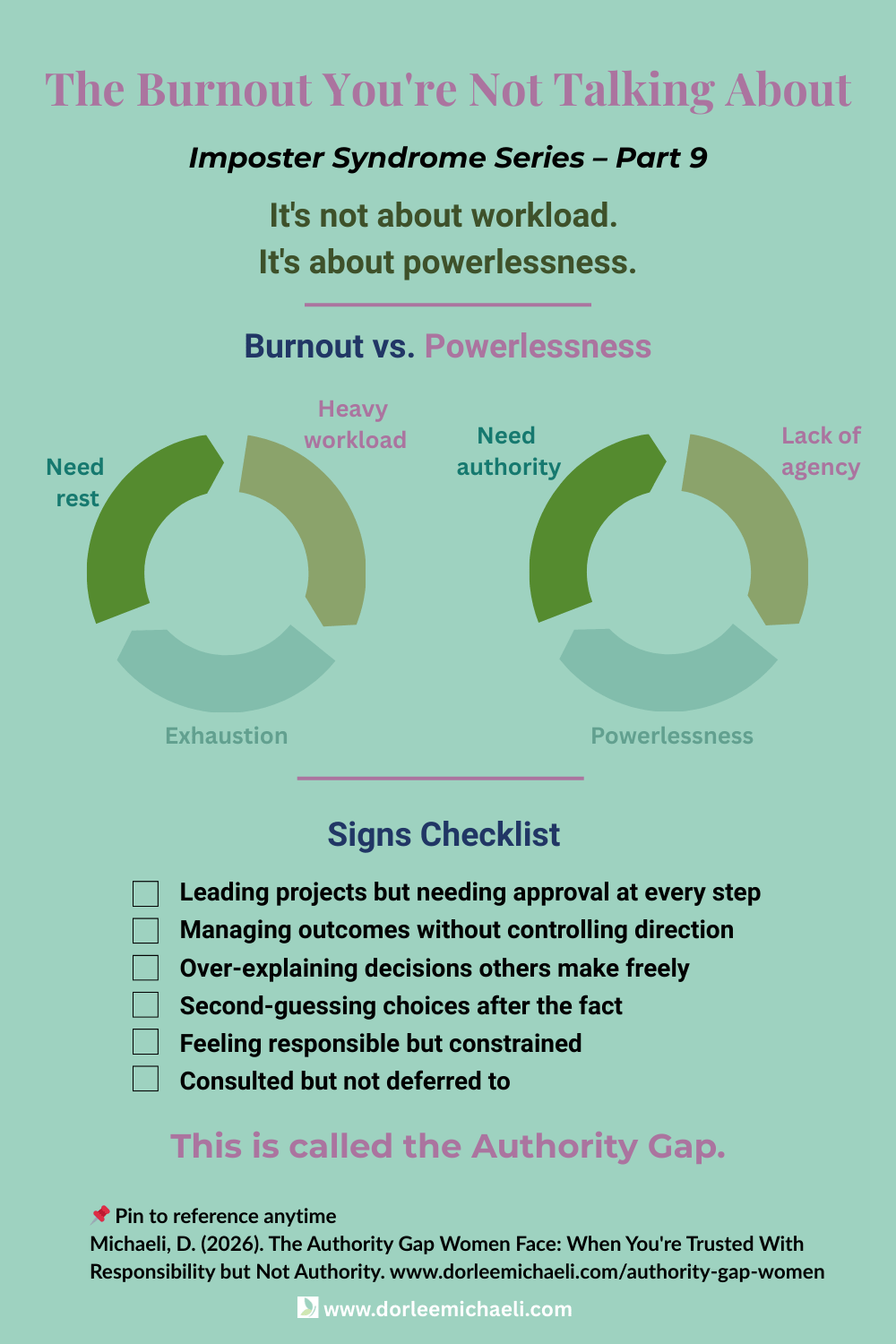

TL;DR: The authority gap describes what happens when capable women are trusted with responsibility but not with power. You’re asked to lead projects and carry outcomes, but still feel the need to over-explain decisions and seek approval for things you already know. This post examines why this structural pattern forms and how it differs from imposter syndrome.

Trusted with responsibility but not authority? You’re experiencing the Authority Gap, and you’re not alone.

You may be trusted to carry outcomes and responsibility, while still needing approval for decisions you’re fully qualified to make.

Many high achieving women reach a confusing point in their careers. This is the authority gap women in leadership face, a pattern where competence and power don’t align.

They are visible.

They are competent.

They are trusted to carry responsibility.

And yet, when it comes to authority, something does not fully translate.

They are asked to lead projects but not make final decisions.

They are relied on for execution but not invited into real power.

They are consulted but not deferred to.

Over time, this creates a quiet and often unsettling question.

If I am capable and visible, why am I still not trusted to decide?

This experience is not a confidence problem.

It is not a motivation issue.

And it is not simply imposter syndrome.

It is something else.

Journalist Mary Ann Sieghart coined the term ‘authority gap’ to describe how women’s expertise is systematically undervalued. The authority gap women face in leadership is a specific manifestation: being trusted with responsibility while denied authority.

What the Authority Gap Is (and Why It’s So Often Misunderstood)

The phrase “authority gap” has been used more broadly to describe gender based credibility gaps in public and professional life. Journalist Mary Ann Sieghart’s work, for example, explores how women’s expertise is systematically undervalued across institutions.

In this piece, the term is used more narrowly and clinically.

Here, the Authority Gap refers to a specific psychological and relational dynamic in which capable women are

trusted with responsibility but not granted corresponding authority.

The authority gap women navigate is both structural and psychological, shaped by gendered expectations and organizational dynamics. They carry outcomes, risk, and accountability, while decision making power remains constrained.

This distinction matters.

The internal experience of holding responsibility without authority has unique emotional and nervous system consequences. When misunderstood, it is often mislabeled as self doubt or lack of confidence.

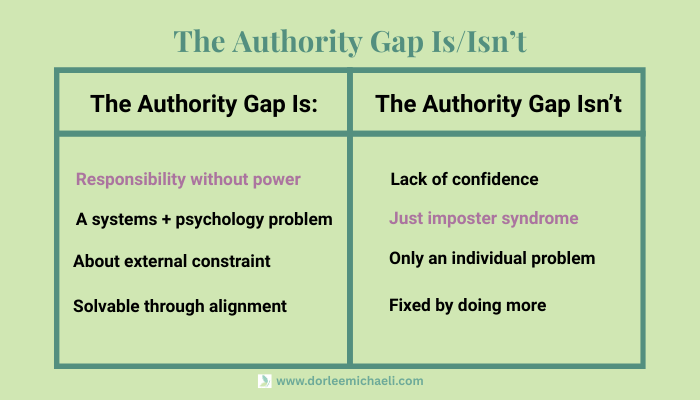

Why This Is Not Just Imposter Syndrome

Imposter syndrome focuses on internal doubt.

The Authority Gap focuses on a mismatch between internal capacity and external power.

Many women living inside this gap do not question their competence.

They know they are capable.

They have evidence.

They have a track record.

What they question is whether they are allowed to take up authority.

When everything is framed as imposter syndrome, the burden of change quietly shifts onto the individual.

Think differently.

Be more confident.

Speak up more.

But the Authority Gap exists at the intersection of psychology, relationships, and systems.

It asks a different question.

What happens when someone is capable, visible, and contributing, yet authority is still withheld?

How the Authority Gap Develops

The Authority Gap rarely appears suddenly.

It develops over time through overlapping internal and external forces.

When You’re Trusted with Responsibility But Not Authority: The Early Signs

Gendered expectations around leadership

Leadership is still unconsciously associated with certain traits.

Decisiveness expressed quickly.

Confidence displayed visibly.

Authority signaled through dominance.

Quiet competence is often misread as support rather than leadership.

Thoughtfulness can be mistaken for hesitation.

Relational awareness may be interpreted as uncertainty.

Women who lead calmly and collaboratively may be valued while simultaneously overlooked. This is how the authority gap women face becomes embedded in organizational culture.

Research reveals a particularly painful dynamic: when women demonstrate clear competence and success, they

are judged as equally capable as their male counterparts, but significantly less likable. This “double bind” directly affects access to organizational rewards, including promotions, raises, and decision-making authority.

Organizational and structural contributors

The Authority Gap is not created by psychology alone. It is often reinforced by organizational structures that separate responsibility from decision making power.

Common examples include:

- Roles that carry delivery responsibility without authority

- Decision making that occurs in closed or informal networks

- Lack of sponsorship despite strong performance

- Hierarchies that concentrate authority at higher levels while distributing responsibility downward

In these environments, women are positioned as reliable operators rather than authoritative leaders, regardless

of competence. These structural patterns explain why authority gap women encounter persists even in progressive organizations.

Burnout research has consistently identified lack of control as a critical factor in job-person mismatch. When

employees cannot influence decisions that affect their work or exercise professional autonomy, they experience

significantly higher rates of burnout and disengagement, regardless of workload.

Over time, a subtle message forms.

You are trusted to execute.

You are not trusted to decide.

When this pattern repeats, it shapes internal expectations even in highly capable professionals.

Early conditioning around approval and safety

Many high achieving women learned early that being liked and being safe were connected.

They became skilled at reading rooms.

They learned to anticipate needs.

They learned to smooth friction.

These skills are adaptive and valuable.

They also contribute to the authority gap women face when trying to claim authority later.

When authority feels relationally risky, women may soften their stance or defer, even when fully qualified to

lead.

Trauma informed survival patterns

For some women experiencing the Authority Gap, earlier relational experiences play an important role. This is

not true for everyone, and authority gaps do not automatically indicate a trauma history.

However, for women who have lived through relational trauma or chronic emotional invalidation, authority can

activate deeper nervous system responses.

Visibility without safety can feel dangerous.

Deciding without consensus can feel exposing.

Taking up space can trigger fear of rupture or rejection.

In these cases, the Authority Gap is not about ambition.

It is about protection.

The body remembers that authority once came with cost.

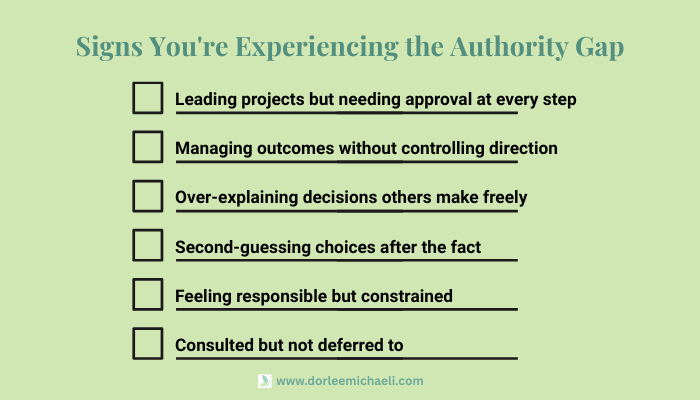

How the Authority Gap Feels Internally

Women living inside this gap often describe a specific internal experience.

They feel responsible but constrained.

Visible but not powerful.

Relied on but not backed.

These are the internal markers of the authority gap women describe in therapy

- Over explaining decisions

- Seeking permission for things they already know

- Second guessing choices after the fact

- Delaying strong opinions until invited

Not because clarity is missing.

But because authority has not been consistently mirrored back.

This creates cognitive dissonance.

I am trusted to do this work.

But not trusted to decide how it should be done.

That dissonance slowly erodes self trust, even in confident and capable women.

Why Doing More Does Not Close the Gap

One of the most painful beliefs about the Authority Gap is that it can be solved by effort.

If I do more, they will trust me.

If I prove myself again, it will shift.

If I am flawless, authority will follow.

But authority is not earned through over functioning. Understanding this is crucial for authority gap women who’ve been told that working harder will eventually translate to power.

In fact, doing more often reinforces the gap.

When responsibility is absorbed without renegotiating authority, systems learn that the imbalance works. The

work gets done. The structure remains unchanged.

This is not a personal failure.

It is a relational pattern.

The Psychological Cost of the Authority Gap (and Why It Leads to Burnout)

The authority gap women experience takes a measurable psychological toll.

Emotionally, it leads to frustration and quiet resentment.

Cognitively, it fuels rumination and self monitoring.

Physiologically, it keeps the nervous system in a state of alert.

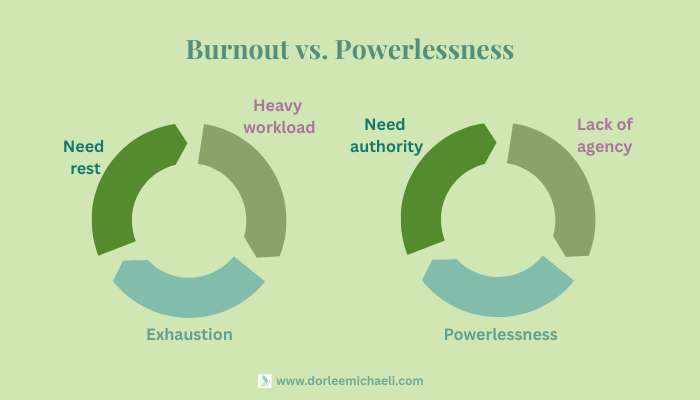

Many women experience burnout not only from workload, but from lack of agency.

This distinction is critical.

Burnout is not always about exhaustion.

Sometimes it is about powerlessness.

Current burnout research confirms this: burnout comprises multiple dimensions beyond exhaustion, including

cynicism and a profound sense of ineffectiveness. The inability to influence outcomes or exercise professional

autonomy sits at the heart of this inefficacy dimension.

When the Authority Gap persists, women may feel essential to their organizations while simultaneously feeling

invisible in rooms where decisions are made.

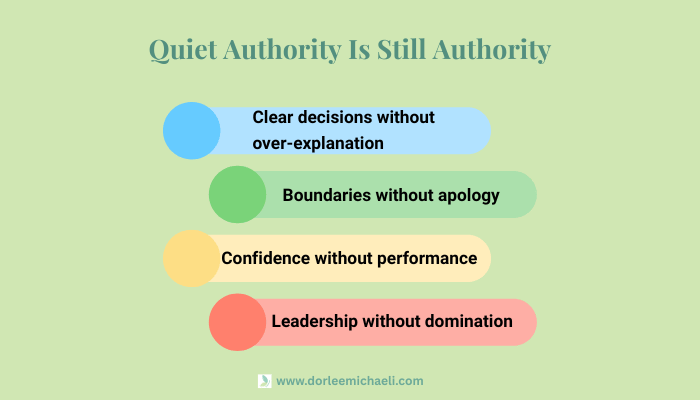

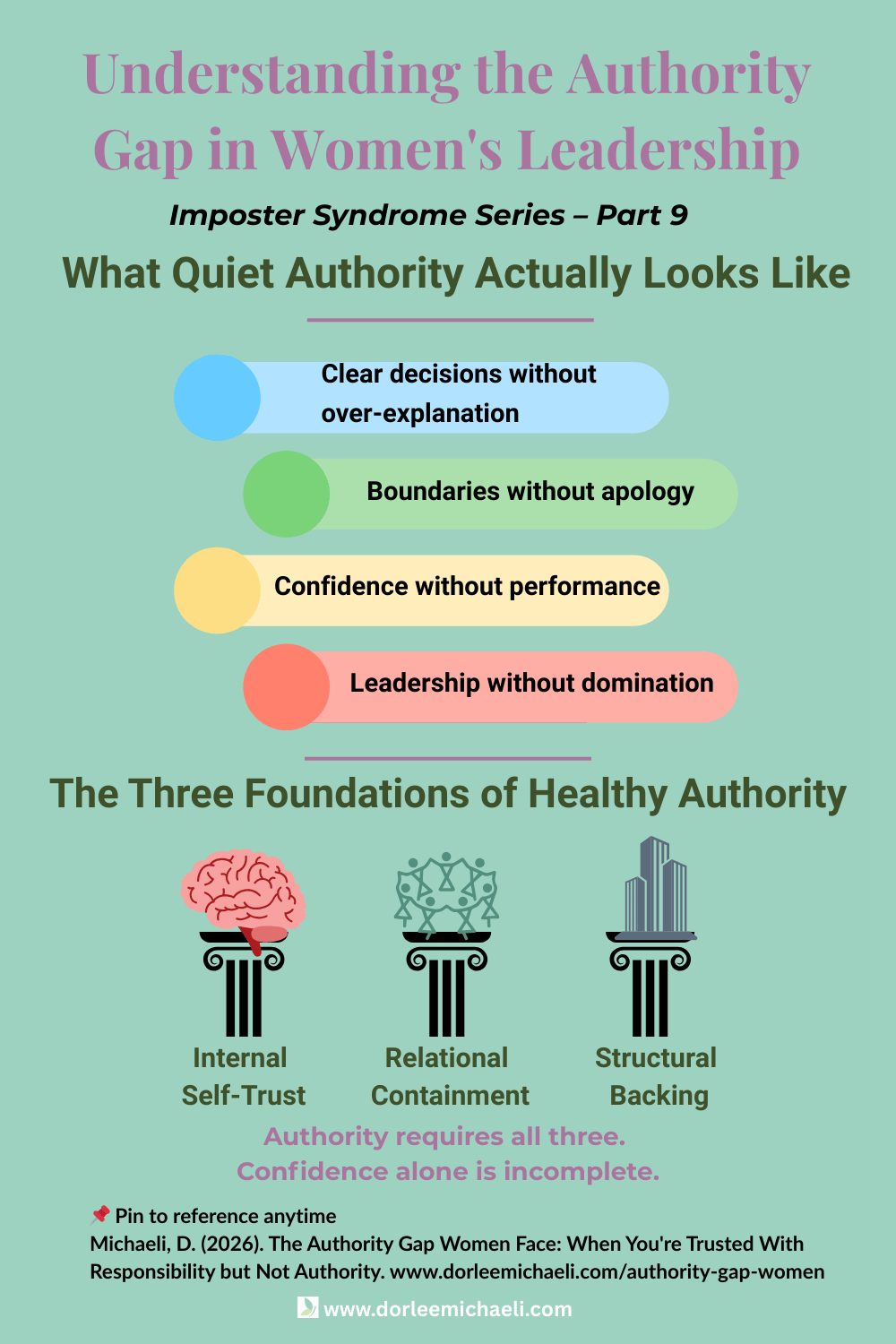

Reframing Authority: It’s Not Dominance or Confidence

A meaningful shift begins with redefining what authority actually is.

Authority is not dominance.

It is not volume.

It is not certainty performed for others.

Authority is the capacity to decide and be supported in that decision.

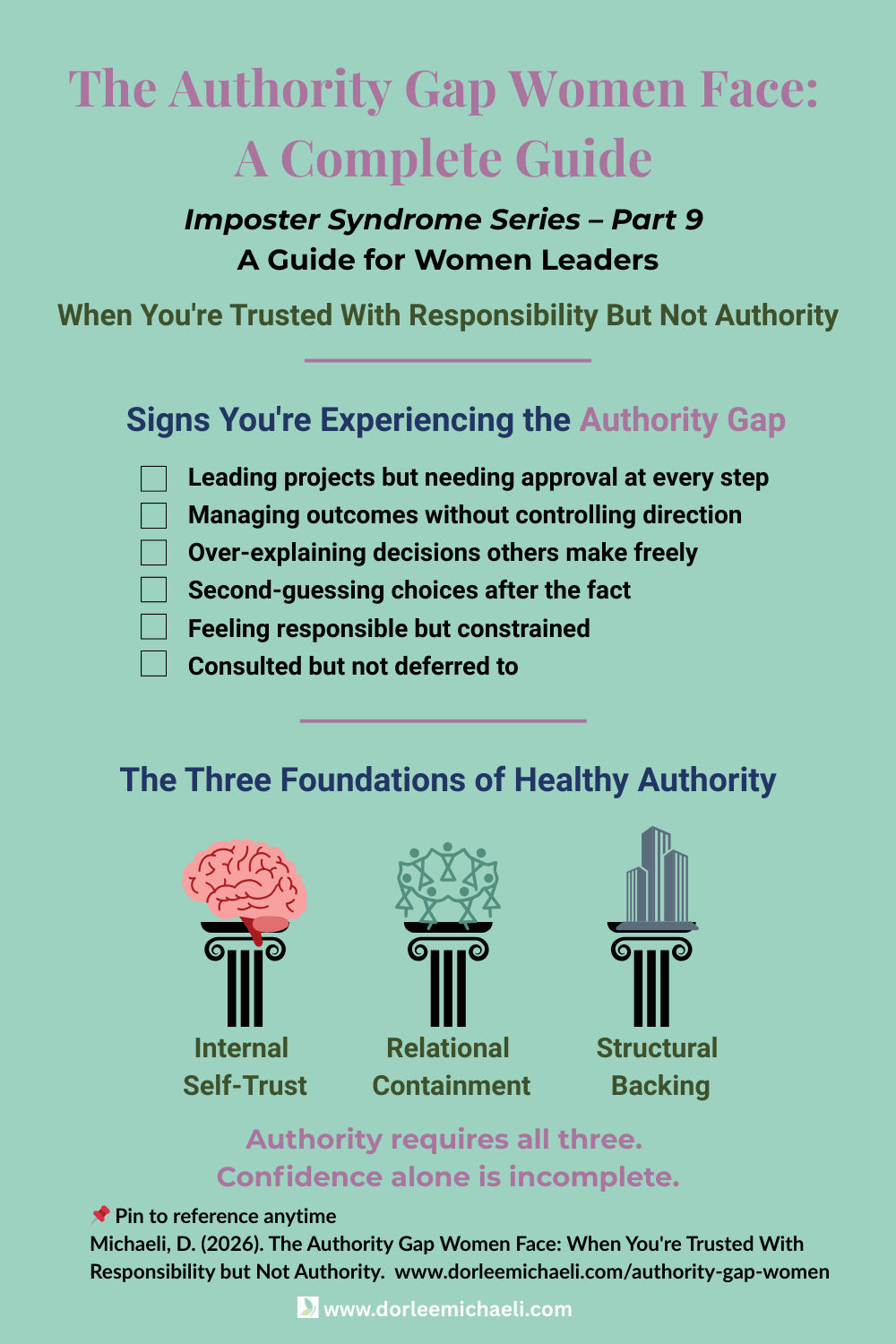

Healthy authority rests on three foundations:

- Internal self trust

- Relational containment

- Structural backing

Many women focus on internal confidence alone.

That work matters.

It is also incomplete.

Without relational and structural support, authority remains fragile.

Where Therapy Can Help (and Where It Can’t)

Therapy does not exist to fix confidence.

For women navigating the Authority Gap, therapy supports alignment.

This work may include:

- Identifying where authority was learned to be unsafe

- Understanding how survival patterns show up in leadership roles

- Strengthening internal permission to decide

- Increasing tolerance for relational discomfort

- Clarifying where external boundaries are needed

In trauma informed therapy, the nervous system is central. When authority was learned to be unsafe, EMDR therapy can help reprocess these experiences and rebuild a sense of safety around decision-making power.

When authority feels dangerous, the body signals restraint even when the mind is ready.

Healing the Authority Gap requires working with both.

MOVING FORWARD WITHOUT BECOMING SOMEONE ELSE

Many women share a quiet fear.

If I claim authority, I will lose myself.

They worry about becoming rigid, aggressive, or disconnected.

But authority does not require abandoning relational values.

Quiet authority is still authority. This reframe is essential for authority gap women who fear that claiming power means abandoning their values.

It looks like:

Clear decisions without over explanation

Boundaries without apology

Con>dence without performance

Leadership without domination

The goal is not to become louder.

It is to become more internally aligned.

A Closing Reflection

If you are trusted with responsibility but not authority, pause before turning inward.

Ask a different question.

Where is there a mismatch between what I carry and what I am allowed to decide?

That question opens space for clarity rather than self blame.

If you’re one of many authority gap women navigating this dynamic, know this: it is not a flaw. It is a signal.

And like all meaningful signals, it deserves careful attention.

If you’re ready to explore how therapy can help you navigate the authority gap women face, learn more about my approach or discover how EMDR therapy can help you reclaim your authority.

The authority gap isn’t imposter syndrome; it’s a structural pattern where competence doesn’t translate to authority. Unlike the internal patterns we’ve explored (rooted in nervous system and early conditioning), the Authority Gap is an external barrier that requires both personal boundary-setting and organizational change. Final post coming next.

Authority Gap FAQs

The Authority Gap describes a pattern where capable women are trusted with responsibility, outcomes, and accountability, but not granted corresponding decision-making power or authority.

Imposter syndrome is an internal pattern rooted in early conditioning and nervous system responses.

The Authority Gap is an external structural barrier; it’s what happens when organizations give women accountability without power.

One requires internal rewiring; the other requires both personal boundary-setting and organizational change.

The Authority Gap is not about readiness or competence.

Ask yourself:

- Am I repeatedly asked to lead initiatives but need approval at every step?

- Do I have peers with similar experience who are given more autonomy?

- Am I managing complex outcomes without control over strategic direction?

- Do I find myself over-explaining decisions that others make without justification?

If you’re early in your career, it’s natural to have less authority.

The Authority Gap shows up when your responsibility significantly outpaces your power to decide, and this pattern persists despite proven competence.

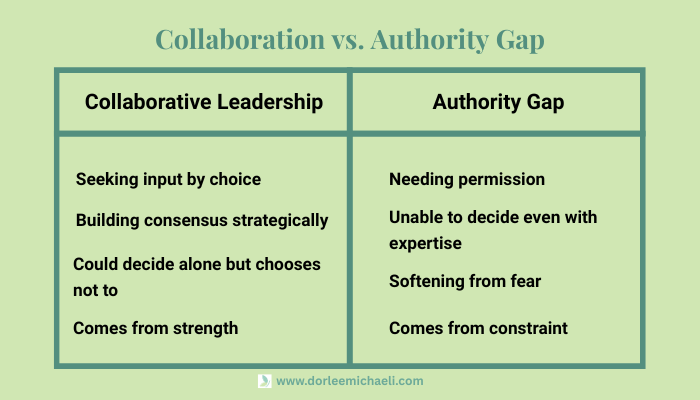

Seeking input is collaborative leadership. Needing permission is different.

Collaborative decision-making involves:

- Gathering perspectives to make informed choices

- Building buy-in for implementation

- Considering impact on stakeholders

- Making the final call with confidence

The Authority Gap shows up when:

- You know what should be done but wait for validation

- You second-guess clear decisions after the fact

- You seek approval for choices well within your expertise

- You feel you need permission rather than wanting input

The distinction is internal: Are you gathering information to decide, or are you uncertain whether you’re allowed to decide at all?

Collaboration is a leadership style. The Authority Gap is a constraint on power.

Collaborative leaders intentionally seek input and build consensus as part of how they lead. They choose this approach and could make unilateral decisions if needed.

The Authority Gap is characterized by:

- Feeling unable to make decisions even when you have the expertise

- Softening your stance not by choice but from fear of relational consequences

- Deferring when you don’t want to but feel you should

- Absorbing responsibility without the structural backing to actually lead

Collaborative leadership comes from strength and choice. The Authority Gap comes from constraint and adaptation.

Yes. Research shows that powerlessness (not workload) is one of the strongest predictors of burnout.

When you carry full responsibility without corresponding authority, you’re constantly working harder to prove yourself, over-explaining decisions, and absorbing the emotional labor of navigating around your lack of power.

This creates chronic stress and exhaustion.

This is one of the hardest questions because it requires facing structural reality.

First, get clear on what you can control:

- Your internal permission to have clear opinions

- Your ability to state positions without over-explaining

- Your boundaries around what you will and won’t absorb

- Your tolerance for relational discomfort when you assert yourself

Then, assess what’s organizationally changeable:

- Can you negotiate for specific decision-making rights?

- Is there a sponsor who could advocate for structural changes?

- Are there projects where you could demonstrate autonomous leadership?

If the organization consistently refuses to match authority with responsibility despite your advocacy, you face a decision about whether the cost of staying is sustainable.

Sometimes the most powerful act is recognizing when a system cannot give you what you need, and choosing to find one that will.

“Leaning in” can be part of the solution, but it’s not the whole answer.

The Authority Gap exists at the intersection of internal patterns, relational dynamics, and structural barriers.

If you focus only on individual assertiveness without addressing how your nervous system responds to authority, whether your relationships can tolerate your authority, and whether your organization structurally supports, you may end up pushing harder in a system designed to resist you.

This often leads to exhaustion and self-blame.

Meaningful change requires working on all three levels: internal alignment, relational repair or renegotiation, and structural advocacy or repositioning.

Yes, and here’s why.

Therapy can’t change your organization’s structure. But it can help you:

- Identify where you’ve internalized constraints that aren’t actually there

- Distinguish between systemic barriers and personal patterns

- Build capacity to tolerate the discomfort of claiming authority

- Develop clarity about which battles are worth fighting

- Recognize when a system truly cannot meet your needs

- Strengthen your ability to hold boundaries and make decisions

- Process the grief or anger that comes with facing structural limitations

Therapy helps you show up with more internal alignment and relational capacity, even if the external system doesn’t change immediately.

And sometimes, that internal shift is what makes it possible to either transform the system or find a better fit elsewhere.

This is a legitimate fear, and it’s worth examining carefully.

Healthy professional relationships can tolerate your authority. They may need to adjust, and there may be temporary discomfort, but they fundamentally remain intact.

If claiming appropriate authority consistently damages relationships, that’s important information:

- The relationship may have been built on you staying small

- The other person may be invested in the power imbalance

- The organizational culture may punish women’s authority

Sometimes relationships do change when you claim authority. But ask yourself:

- Are these relationships built on mutuality, or on you deferring?

- Are you losing relationships, or are you losing approval?

- What is the cost of maintaining relationships that require you to diminish yourself?

The relationships worth keeping can handle your growth. The ones that can’t were never built to support your full leadership.

References:

Heilman, M. E. (2012). Gender stereotypes and workplace bias. Research in Organizational Behavior, 32, 113–135. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.riob.2012.11.003

Ibarra, H., Ely, R., & Kolb, D. (2013). Women rising: The unseen barriers. Harvard Business Review, 91(9), 60–66.

Maslach, C., & Leiter, M. P. (2016). Understanding the burnout experience: Recent research and itsimplications for psychiatry. World Psychiatry, 15(2), 103–111. https://doi.org/10.1002/wps.20311

Porges, S. W. (2011). The polyvagal theory: Neurophysiological foundations of emotions, attachment, communication, and self-regulation. W. W. Norton & Company.

Sieghart, M. A. (2021). The authority gap: Why women are still taken less seriously than men, and what we can do about it. Doubleday.

Van der Kolk, B. (2014). The body keeps the score: Brain, mind, and body in the healing of trauma. Viking.

This really captures something I’ve seen (and felt) so many times but didn’t have a word for. Being trusted to carry the weight but not given real authority is such a quiet mind-twister. I appreciate how clearly you separate this from confidence or imposter syndrome… that distinction matters. This is one of those pieces that makes you pause and say, “Oh, that’s what’s been going on.” Thanks for putting words to it.

Thank you, Cheryl. I really appreciate you naming that. “Being trusted to carry the weight without real authority” can be such a quiet mind-twister, and without language for it, it’s easy to misread it as a personal shortcoming. I’m glad the distinction landed and offered that moment of clarity.

The authority gap is often misdiagnosed.

It is not, at its core, a confidence gap or a competence gap. Nor is it solved by women speaking up more, leaning in, or endlessly adjusting tone.

The authority gap is an ontological one. It lives in the space between how authority is embodied, interpreted, and legitimised, and who is culturally permitted to occupy that space without penalty.

Many women already speak clearly, take responsibility, and carry weight. What is missing is not voice, but recognition.

The same behaviour that reads as leadership in a man is too often read as abrasive, emotional, or excessive in a woman. When women soften, they are overlooked. When they are firm, they are judged. When they adapt, the bar moves again.

This is not an individual failing. It is systemic.

Organisations still operate with largely unexamined assumptions about what authority looks like and who is allowed to hold it without social cost. These assumptions are reinforced daily in feedback, meetings, promotion decisions, and informal narratives.

The real work is not teaching women to manage themselves better inside broken frames. It is redesigning the frames.

When authority is re-anchored in contribution, responsibility, and impact rather than gendered expectation, women do not need to close the gap.

The gap dissolves.

Beautifully said, Fiona. This captures exactly why confidence-based solutions keep failing. When authority is culturally mediated and unevenly legitimized, effort and clarity don’t close the gap—they expose it. Until organizations examine how authority is interpreted and sanctioned, the burden keeps falling on individuals instead of systems.

Oooh this is an interesting angle that I haven’t heard before… the authority gap makes alot of sense. So is the solution to stop being a doer and start being a decider? or how does that work?

Not exactly, Chelsea. The shift isn’t from doing to deciding. It’s from being accountable without authority to having decision rights match responsibility. Many women are already deciding informally. The issue is that their decisions aren’t legitimized or protected by the system.

The “authority gap” shows up in tiny words, “just,” “maybe,” “I think,” “sorry,” “I could be wrong.” They sound polite, but they can make a strong idea sound unsure.

I used to do this too. I would add “I could be wrong” before sharing my point, just to feel safe. It did not help me. It trained people to doubt me before I even finished.

One simple fix is to say the point first, then give the reason.

For example: “My recommendation is X, because Y.”

No extra soft words needed.

This is such an important observation, Sandra. Those words are rarely about uncertainty in the idea. They’re about uncertainty in how the idea will be received. Saying the recommendation first is powerful, and it also exposes whether the system can actually tolerate clear authority.

Wow – amazing post. You are so right. I have worked harder, over think things and over explain, over function, said yes too many times, and now I am exhausted and burnt out. Thank you for sharing and saying the words. It all makes sense to me.

I’m really glad it helped put language to what you’ve been living, Sheryl. Overworking, over-explaining, and over-functioning often start as smart adaptations, but they quietly become exhausting over time. Making sense of it is an important first step toward doing things differently.